176

PERMA: SCOPING AND ADDRESSING THE PROBLEM OF

LINK AND REFERENCE ROT IN LEGAL CITATIONS

Jonathan Zittrain, Kendra Albert, and Lawrence Lessig

∗

I

NTRODUCTION

Works of scholarship have long cited primary sources or academic

works to provide sources for facts, to incorporate previous scholarship,

and to bolster arguments. The ideal citation connects an interested

reader to what the author references, making it easy to track down,

verify, and learn more from the indicated sources.

In principle, as cited sources move to the Web, this linking should

become easier. Rather than requiring a reader to travel to a library to

follow the sources cited by an author, the reader should be able to re-

trieve the cited material immediately with a single click.

But again, only in principle. The link, a URL, points to a resource

hosted by a third party. That resource will only survive so as long as

the third party preserves it. And as websites evolve, not all third par-

ties will have a sufficient interest in preserving the links that provide

backwards compatibility to those who relied upon those links. The

author of the cited source may decide the argument in the source was

mistaken and take it down. The website owner may decide to aban-

don one mode of organizing material for another. Or the organization

providing the source material may change its views and “update” the

original source to reflect its evolving views. In each case, the citing

paper is vulnerable to footnotes that no longer support its claims. This

vulnerability threatens the integrity of the resulting scholarship.

This problem does not exist for printed sources, or at least not in

the same way. Print sources can be kept indefinitely by libraries or ar-

chives, assuming space and other determinations allow. The ability to

update those original print sources is, for these purposes, happily diffi-

cult. Tracking down every original copy of an edition of a printed

New York Times and changing a story on page A4 is the stuff of

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

∗

Jonathan Zittrain is Professor of Law at Harvard Law School and the Kennedy School of

Government, and Professor of Computer Science at the Harvard School of Engineering and Ap-

plied Sciences. Kendra Albert is a JD candidate at Harvard Law School. Lawrence Lessig is the

Roy L. Furman Professor of Law and Leadership at Harvard Law School, and Director of the

Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics at Harvard University. We thank research assistants Nicholas

Fazzio, Benjamin Sobel, Leonid Grinberg, and Shailin Thomas for their work, Constantine

Boussalis for statistical assistance, and Raizel Liebler and Martin Klein for their helpful feedback.

The authors recognize the efforts of the Harvard Law School Library Innovation Lab, in particu-

lar Kim Dulin, Matthew Phillips, Annie Cain, and Jeff Goldenson, in taking Perma from idea to

reality.

2014] PERMA 177

Orwell’s imagination, not real-world practicality. But to do the same

thing with an online edition is trivial.

As newspapers, government agencies and other non-academic

sources move to primarily digital publication, law review articles in-

creasingly reference online materials, sometimes in lieu of, or in addi-

tion to, a print source.

1

When online material does not have a formal

paper counterpart such as a published book or journal article, there

are few repositories that keep copies of the linked material from cita-

tions. Instead, linked material remains in the custody of its single host,

rather than being distributed among libraries or readers.

Because of this, materials at links frequently (1) become inaccessi-

ble or (2) change, a phenomenon known as “link rot” and “reference

rot,” respectively. Link rot refers to the URL no longer serving up any

content at all. Reference rot, an even larger phenomenon, happens

when a link still works but the information referenced by the citation

is no longer present, or has changed.

2

Building on previous studies of link rot,

3

we have reviewed links

published within three legal journals — the Harvard Law Review

(HLR), the Harvard Journal of Law and Technology (JOLT) and the

Harvard Human Rights Journal (HRJ) — as well as the links con-

tained across all published United States Supreme Court opinions. We

exploited the unique citation style of law reviews and court opinions,

including the extensive cite-checking process, which meant that in al-

most all cases, we were able to determine whether the original infor-

mation was present. Thus, our study was able to validate previous

findings of link rot in law review and Supreme Court citations, as well

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

1

For example, The Bluebook style guide for legal citation says: “The Bluebook requires the

use and citation of traditional printed sources when available, unless there is a digital copy of the

source available that is authenticated . . . .” T

HE

B

LUEBOOK

: A U

NIFORM

S

YSTEM

OF

C

ITATION

R.

18

.

2

, at

165 (Columbia Law Review Ass’n et al. eds., 19th ed. 2010).

2

The Hiberlink and Memento project team at Los Alamos National Lab helpfully distin-

guishes between the two phenomena — a useful distinction that we import. See Robert Sander-

son, Mark Phillips, & Herbert Van de Sompel, Analyzing the Persistence of Referenced Web Re-

sources with Memento,

AR

X

IV

(May 17, 2011, 7:21 PM), http://arxiv.org/abs/1105.3459, archived

at http://perma.cc/0ee5QbGfp5F.

3

E.g., Helane E. Davis, Keeping Validity in Cite: Web Resources Cited in Select Washington

Law Reviews, 2001–03, 98 L

AW

L

IBR

. J. 639 (2006); Raizel Liebler & June Liebert, Something

Rotten in the State of Legal Citation: The Life Span of a United States Supreme Court Citation

Containing an Internet Link (1996–2010), 15 Y

ALE

J.L. & T

ECH

. 273 (2013); Mary Rumsey, Run-

away Train: Problems of Permanence, Accessibility, and Stability in the Use of Web Sources in

Law Review Citations, 94 L

AW

L

IBR

. J. 27 (2002); Wallace Koehler, A Longitudinal Study of Web

Pages Continued: A Consideration of Document Persistence, 9 I

NFORMATION

R

ESEARCH

, (Jan.

2004), http://informationr.net/ir/9-2/paper174.html, archived at http://perma.cc/8767-F7NG; John

Markwell & David W. Brooks, “Link Rot” Limits the Usefulness of Web-based Educational Mate-

rials in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 31 B

IOCHEMISTRY

&

M

OLECULAR

B

IOLOGY

E

DUC

. 69 (2003), available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/bmb.2003.494031010165/

full, archived at http://perma.cc/N969-86A4.

178 HARVARD LAW REVIEW FORUM [Vol. 127:176

as provide an estimate of how many said citations were affected by

reference rot.

We documented a serious problem of reference rot: more than 70%

of the URLs within the above mentioned journals, and 50% of the

URLs within U.S. Supreme Court opinions suffer reference rot —

meaning, again, that they do not produce the information originally

cited.

Given both of these problems, in this paper we propose a solution

for authors and editors of new scholarship that will secure the long-

term integrity of cited sources by involving libraries in a distributed,

long-term preservation of link contents.

Perma.cc, developed by the Harvard Library Innovation Lab, is a

caching solution to be used by authors and journal editors in order to

integrate the preservation of cited material with the act of citation.

Upon direction from a paper author or editor, Perma will retrieve and

save the contents of a webpage, and return a permanent link. When

the work is published, the author can include that permanent citation

in addition to a citation to the original URL, or just the permanent

link, ensuring that even if the original is no longer available because

the site goes down or changes, the cache is preserved and available.

Other services have offered permanent citations before.

4

But those

services themselves become vulnerabilities within a citation system if

their own long-term viability is not assured. Perma mitigates this vul-

nerability by distributing the Perma caches, architecture, and govern-

ance structure to libraries across the world. Thus, so long as any li-

brary or successor within the system survives, the links within the

Perma architecture will remain.

P

REVIOUS

W

ORK

Much of the previous research on link rot was done in the early

2000s as citation of online materials rapidly increased. In 2002, Pro-

fessor Mary Rumsey studied citations in legal materials, and concluded

that as the citation of URLs was increasing, so too was link rot.

5

At

the time of her 2002 study she found a steady decrease in working

links, with 61% of links from articles published in the previous year

working, to only 30% working from five years earlier.

6

Other studies, including by Professor Wallace Koehler from 2004,

and by Professors John Markwell and David Brooks from 2006, are

consistent with Rumsey’s results, but apply to other domains: general

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

4

W

EB

C

ITE

, http://www.webcitation.org, archived at http://perma.cc/0p7xfMNg8Kf.

5

Rumsey, supra note 3, at 32, 34–35.

6

Id. at 35. Rumsey defines working links as links that take a viewer to the document or take

a viewer to a list where the document appears. Id. at 31.

2014] PERMA 179

webpages and biochemistry, respectively.

7

More recent work, includ-

ing that of the Chesapeake Digital Preservation Group (CDPG) and

Raizel Liebler and June Liebert’s study of Supreme Court citations,

recently published in the Yale Journal of Law and Technology, have

concluded that link rot remains a significant problem.

8

The CDPG has taken another approach to the study of link rot,

while also taking important steps to preserve online resources.

9

The

CDPG does not seek to evaluate the link rot of a specific set of cita-

tions. Rather, since 2007, the CDPG has been caching documents that

it anticipates might be used as legal resources, specifically for the pur-

poses of studying link rot.

10

Librarians associated with the CDPG se-

lect resources that they believe are worth collecting, and save a copy of

those resources on their servers.

11

When conducting their link rot re-

search, the team then compares the pages currently hosted at a URL

with the cached copy.

12

The CDPG’s work is the most conclusive of the studies reviewed,

due to its caching and comparison of digital resources. In its 2013 re-

port, the CDPG found that 44% of the URLs from its original data set,

including content collected between 2007 and 2008, no longer

worked.

13

The report does not mention whether a percentage of the

links underwent reference rot — the content changing but the URL

still resolving correctly. The CDPG also found that link rot in the

sample was increasing over time.

14

It may be difficult, however, to generalize the Chesapeake findings

to more general legal citations, or to scholarship more broadly. The

material captured by Chesapeake is specifically selected by archivists

and librarians based on continuing relevance to legal scholarship. For

example, Chesapeake’s preserved documents include prepared pam-

phlets on government employee health insurance, a Soros report on

HIV transmission criminalization, and a 1940 statement on principles

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

7

Koehler, supra note 3; Markwell & Brooks, supra note 3, at 70–71.

8

“Link Rot” and Legal Resources on the Web: A 2013 Analysis, C

HESAPEAKE

D

IGITAL

P

RESERVATION

G

ROUP

(2013), http://cdm16064.contentdm.oclc.org/ui/custom/default/

collection/default/resources/custompages/reportsandpublications/2013LinkRotReport.pdf (last vis-

ited Feb. 26, 2014); Liebler & Liebert, supra note 3, at 297–99.

9

Overview, C

HESAPEAKE

D

IGITAL

P

RESERVATION

G

ROUP

,

http://cdm16064.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/about#overview (last visited Feb. 26, 2014), archived at

http://perma.cc/0L5yFmvwjaS; see also Sarah Rhodes, Breaking Down Link Rot: The Chesapeake

Project Legal Information Archive’s Examination of URL Stability, 102 L

AW

L

IBR

. J. 581 (2010).

10

Rhodes, supra note 9, at 582.

11

Id.

12

Id.

13

“Link Rot” and Legal Resources on the Web: A 2013 Analysis, supra note 8.

14

Id.

180 HARVARD LAW REVIEW FORUM [Vol. 127:176

of academic freedom.

15

The materials cited in legal scholarship, on the

other hand, may more typically reference popular media sources or in-

dividual webpages. But independent of the collection style, the

CDPG’s finding that

over 50% of links to websites with government

domains such as .gov and .mil no longer work does not bode well for

citations to U.S. government websites.

16

The work that most closely resembles our model is Liebler and

Liebert’s recently published study, which found that 29% of links cited

in decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1996–2010

were “invalid.”

17

As we will describe, our own tests of Supreme Court

links revealed a much higher percentage of reference rot — 50%. The

discrepancy is tied to three factors.

18

First, we count both link rot and reference rot, while Liebler and

Liebert count link rot only. Their method recorded the frequency with

which a link returned an error page. We took the additional step of

measuring reference rot, by manually examining apparently successful

links to determine whether they produced their original sources.

19

Second, time has elapsed since Liebler and Liebert tested their

links, and even a few months can result in an increase in link rot.

And third, we included two more Supreme Court terms in our data

set (OT 2010 and OT 2011).

O

UR

W

ORK

The threshold question of our work echoes Rumsey’s: Are online ci-

tations in law reviews serving their intended purpose — to permit an

interested reader to access the material cited in the journal?

Our answer is the same, but more conclusive: No. O

f

our

spot

-

checked

sample

,

only

29.9%

of

the

HRJ

links

, 26.8%

of

the

HLR

links

,

and

34.2%

of

the

JOLT

links

contained

the

material

cited

due

to

link

or

reference

rot

. W

e

have

no

reason

to

expect

that

other

journals

are

any

different

.

The links we evaluated in this study are to the open Web — that

part of the Web that is accessible without paywalls or other restriction.

Therefore, we did not check links to closed-access websites requiring

passwords, such as references to well-known legal resources such as

LexisNexis or Westlaw. The citation practices of the three journals we

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

15

All Collections, C

HESAPEAKE

D

IGITAL

P

RESERVATION

G

ROUP

,

http://cdm16064.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/search/collection (last visited Feb. 26, 2014), archived at

http://perma.cc/0SvYRpDG26n.

16

See “Link Rot” and Legal Resources on the Web: A 2013 Analysis, supra note 8.

17

Liebler & Liebert, supra note 3, at 298.

18

One less important additional factor is that our work was limited to resources available on

the open Internet, whereas the Liebler and Liebert work was interested in citation more generally.

19

Liebler & Liebert, supra note 3, at 294.

2014] PERMA 181

tested are consistent with this research goal. At the time we tested the

links, all three journals cited hard-copy versions of sources, such as

cases published in reporters, and journal articles using the Bluebook-

approved method of citation by volume number and printed pagina-

tion.

20

These citations of formal sources tend to omit URLs, anticipat-

ing that, inconvenience aside, readers can access the source in its

printed version, or through an online resource, such as LexisNexis or

Westlaw.

21

Therefore, the “available at” URLs within these journals

tend to link to public news articles, government documents, or other

works not systematically available in print. Some also link directly to

websites as proof of the matter asserted — for example, citing to a

corporate home page or history for information about a corporation

not available from a scholarly source.

22

Because our study involved a more extensive two-step review (first

validating the links, and then for valid links, verifying the material

cited is what was originally intended), we were able to consider a more

general question about link rot: how comprehensive are HTTP status

codes for predicting whether a given webpage is still working? Can

such codes be used to successfully evaluate whether a linked source

has evaporated?

HTTP status codes are sent from the webpage’s server to a brows-

er that attempts to navigate to a page. The most popularly known is

404, or “not found,” but there are a number of others. For example, a

200 means that the server returned a page as expected, and a 503 indi-

cates that the service is unavailable.

23

Status codes are easy to check

in an automated fashion, so a successful attempt at pairing error codes

with content or establishing a baseline understanding of error codes

versus link rot could assist in future studies.

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

20

See the article submission policies of each of the journals: Submissions, H

ARV

. L. R

EV

.,

http://www.harvardlawreview.org/submissions.php (last visited Feb. 26, 2014), archived at

http://perma.cc/42FG-NGWE; Submissions, H

ARV

. H

UM

. R

TS

. J., http://harvardhrj.com/about

/submissions (last visited Feb. 26, 2014), archived at http://perma.cc/8EAA-U5UH; Submissions,

H

ARV

. J.L. & T

ECH

., http://jolt.law.harvard.edu/submissions (last visited Feb. 26, 2014), archived

at http://perma.cc/JVM5-WCMD.

21

See, e.g., T

HE

B

LUEBOOK

: A U

NIFORM

S

YSTEM

OF

C

ITATION

R. 16, at 146 (Columbia

Law Review Ass’n et al. eds., 19th ed. 2010).

22

At the time that we pulled data, the HLR did not include URLs for sources that were acces-

sible in print, like New York Times articles. JOLT uses parallel citations to print available

sources, as does HRJ.

23

Roy T. Fielding et al., Hypertext Transfer Protocol — HTTP/1.1, RFC2616, W

ORLD

W

IDE

W

EB

C

ONSORTIUM

, http://www.w3.org/Protocols/rfc2616/rfc2616-sec10.html (last visited Feb.

26, 2014), archived at http://perma.cc/QP8S-8HJN.

182 HARVARD LAW REVIEW FORUM [Vol. 127:176

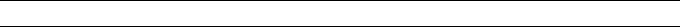

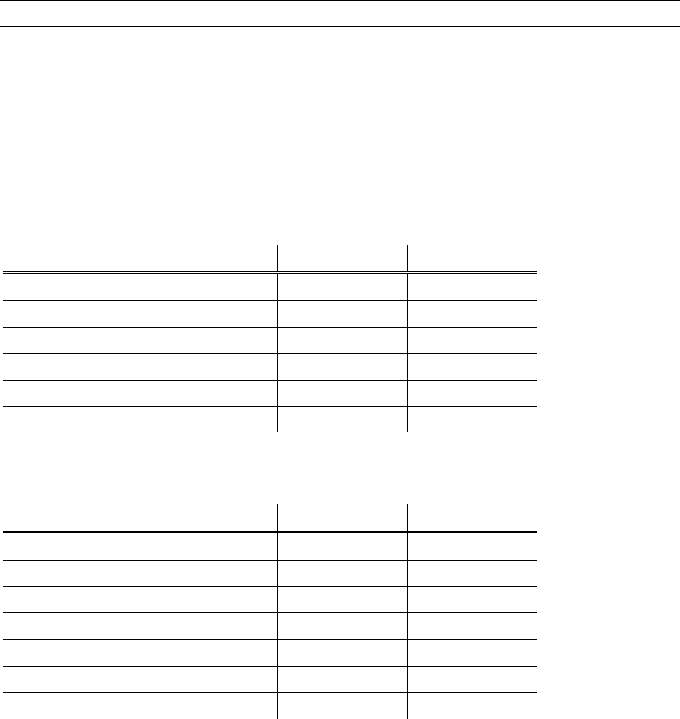

HTTP Status HLR HRJ

J

OLT

200 (working) 350 303 348

OPEN 187 109 191

400 22 --

404 308 253 291

403 65 - 122

All other codes All All All

We found that some error codes are better than others. As ex-

pected, a complete lack of connection, or a 400 or 500 code (including

404, 503, etc.), is almost always a sign of link rot (the only exception

being if a webpage is down temporarily). However, a 200 “all clear”

signal does not mean that a source is present. A 200 can accompany a

page displaying regrets, such as a custom 404-style page deployed by a

website that does not return a 404 status (a soft 404).

24

It can also be a

redirect, such as when a website has been overhauled since the citation

and entire sets of pages have been redirected to the homepage. Of

course, the page can also have changed in content but still be served

up — this being the hardest to detect of the 200 problems and the most

difficult form of reference rot to catch. Of the 353 “200 status” links

within the Supreme Court corpus that we viewed and coded, only 76%

still led to the cited material, indicating that reference rot independent

of link rot is a major problem.

D

ETAILED

M

ETHODOLOGY

AND

D

ATA

Law Review Citations

On September 7, 2012, our team pulled all articles from the Har-

vard Law Review, Harvard Journal of Law and Technology and the

Harvard Law School Human Rights Journal, starting in 1999, 1996,

and 1997, respectively, until the summer of 2012. We isolated all of

the footnotes, and then eliminated all footnotes that did not contain

hyperlinks. Each of the hyperlinks was thus tied to a specific journal

and footnote, and each hyperlink was counted only once. We then ran

an HTTP status check as a first step to determine if the links were no

longer functional, returning an error. If the domain for the URL no

longer existed, the status checker returned a specific error (“OPEN”),

also indicating that link was not functional.

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

24

The term “soft 404” was explained extensively in an earlier paper on web decay. See Z

iv

B

ar

-Y

ossef

,

et

al

., S

ic

T

ransit

G

loria

T

elae

: T

owards

an

U

nderstanding

of

the

W

eb

’

s

D

ecay

,

P

ROC

. 13

TH

I

NT

’

L

C

ONF

.

ON

W

ORLD

W

IDE

W

EB

329 (2004).

2014] PERMA 183

After the HTTP status for all URLs had been coded, we selected a

sample to check by hand. We first determined the proper sample size

for a 5% margin of error for each HTTP status code. We then chose a

random sample that included enough of each type of error code for

each journal.

Each URL marked for spot-checking was loaded into a browser,

and a single research assistant checked the page contents to see if it

matched what the footnote promised. The research assistant coded the

page as working if the URL still returned the expected information,

and as not working if it did not. In most cases, the results were very

easy to determine, given the level of specificity of the footnote and the

contents of the site. However, it was impossible to truly determine in

some cases whether the cited material was still present, in which case

we tended to mark the material as not available. We did not make ef-

forts to retrieve the information if it was not immediately present —

however, some slight parsing mistakes that were introduced during the

URL collection process were fixed.

We also recorded some additional information about the pages

demonstrating reference rot by tagging them to categorize the changes

they revealed. For example, pages that redirected to the home page of

the domain were noted with a “redirect” tag, whereas pages that had

clearly been archived (via a notice in the text of the page) were noted

with an “archive” tag. The tagging process did not include all the pos-

sible variations of reference rot that could happen to linked pages, but

it did allow us to have a better understanding of what happened to

those webpages over the course of time.

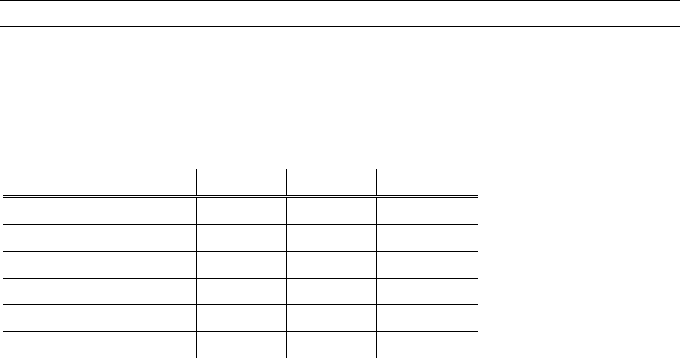

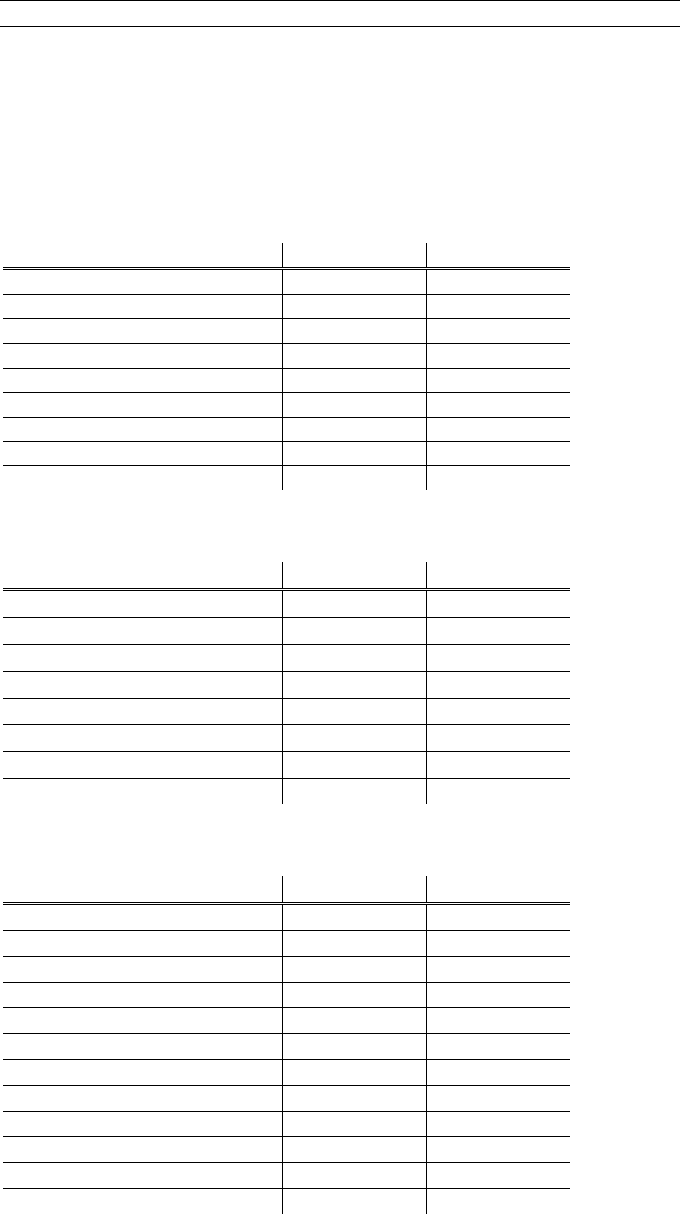

Overall, we found that link rot was a large problem for all three

journals studied. From the initial status code check, only 65% of HLR

links returned a working page (indicated by a “200” code), along with

60% of HRJ links, and 67% of JOLT links. Below are tables with the

status code results from the three journals.

25

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

25

See Appendix 1 for a list of HTTP status code meanings. “OPEN,” which is not an HTTP

status code, means the server did not return anything.

184 HARVARD LAW REVIEW FORUM [Vol. 127:176

Tag HRJ JOLT HLR

200–OK 59.9% 65.2% 66.8%

404–Not Found 31.2% 26.1% 21.9%

OPEN–No Server

Response 6.4% 6.1% 7.0%

403–Forbidden 0.9% 1.3% 3.3%

400–Bad Request 0.5% 0.4% 0.2%

500–Internal Server Error 0.5% 0.4% 0.3%

All Others 0.7% 0.5% 0.8%

Spot-checked data revealed that even pages with no link rot had

undergone reference rot. URLs that appeared to be valid (returning a

200 status code to our status checker) nonetheless frequently redirect to

another page, or were actually 404 pages that did not return the cor-

rect status in the initial check. This is just link rot in disguise. In oth-

er cases, the pages seemed fine, but did not contain the materials that

were originally cited, as in the “Working (updated)” tag, indicating ref-

erence rot.

Only 29.9% of the HRJ links, 26.8% of the HLR links, and 34.2%

of the JOLT links in our sample contained the material cited. Given

that this sample included the ~60% of 200 links, this was much lower

than expected, and significantly different from the numbers expected

based on the status codes. Below is the breakdown of the results from

the spot-check of pages that originally produced a 200 status code.

Tag HRJ

JOLT HLR

200–Working

64% 66% 68%

200–Redirect

22% 15% 14%

200–Custom 404

7% 8% 11%

200–Working (updated)

0% 8% 6%

200–Blank Page

3% 1% 0%

200–Assorted Other

4% 2% 1%

To t al

303 348 350

There was some variation in link rot/reference rot rates by journal,

although it is difficult to tell if this is because of subject material or

due to some other factor, such as publication rates or citation checking.

Of the three journals, JOLT started using hyperlinks in footnotes first.

JOLT and HLR have similar numbers of total hyperlinks; however,

2014] PERMA 185

JOLT publishes twice yearly,

26

and HLR publishes eight times per

year

27

— meaning that per issue, JOLT’s number of links is much

higher. HRJ only publishes once per year.

28

The linked materials do

not differ to significantly across subject fields, however, it may be that

technology websites or news sources of the type cited by JOLT authors

are more careful to preserve URLs then the types of sources included

in HLR or HRJ.

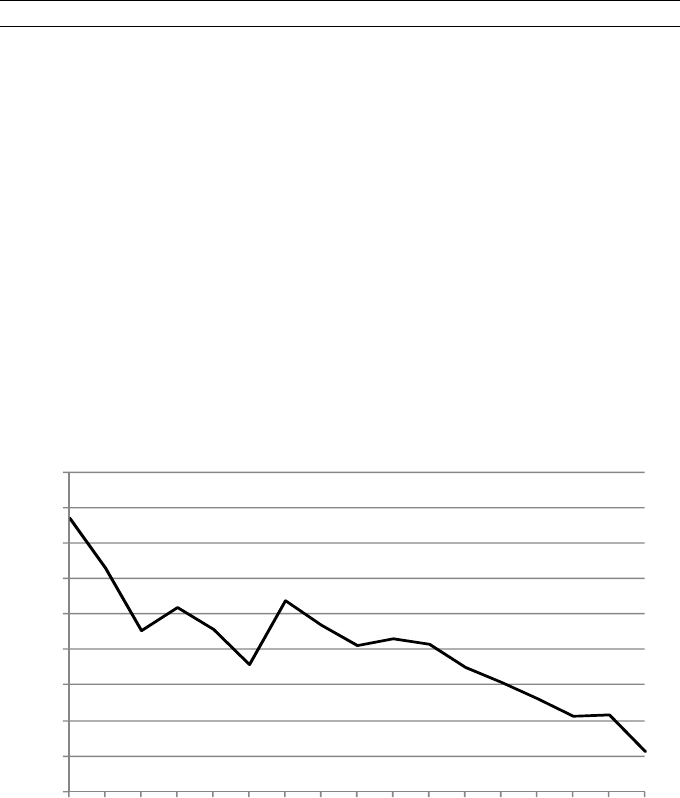

Consistent with previous findings, we also found that the number

of links with either reference or link rot increases with the age of the

publication. The chart below illustrates the percentage of broken links

per year (note that the 2012 data is incomplete):

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

26

Articles, H

ARV

. J.L. & T

ECH

., http://jolt.law.harvard.edu/articles (last visited Feb. 26, 2014),

archived at http://perma.cc/D73W-9AWB .

27

About, H

ARV

. L. R

EV

., http://www.harvardlawreview.org/about.php (last visited Feb. 26,

2014), archived at http://perma.cc/8MCP-F6PX.

28

About, H

ARV

. H

UM

. R

TS

. J., http://harvardhrj.com/about (last visited Feb. 26, 2014), ar-

chived at http://perma.cc/0QMWnM4Lhxs.

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

186 HARVARD LAW REVIEW FORUM [Vol. 127:176

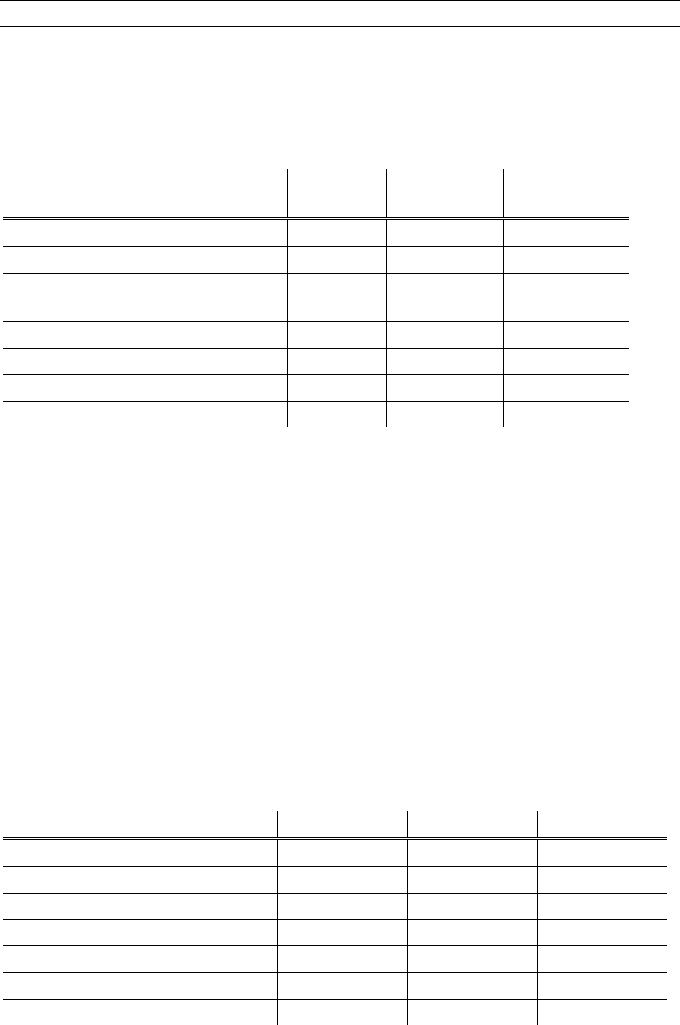

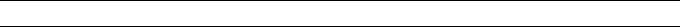

Supreme Court Citations

SCOTUS Status Codes

Tag Count

Percent

200 353 63.6%

OPEN 56 10.1%

404 136 24.5%

403 6 1.1%

Other 4 0.7%

To t al 555

Breakdown of 200 Code URLs

Tag Count

Percent

Cited Material 277 78.5%

Redirect 32 5.8%

Blank Page 3 0.5%

Custom 404 29 5.2%

Updated 5 0.9%

Other 7 1.3%

To t al 353

On June 26, 2013, our team obtained a database of all Supreme

Court opinions from CourtListener.

29

We then found all of the URLs

in that text, first by using a regular expression search technique to

identify all links, and second, by checking the data by hand to elimi-

nate duplicates. This returned 555 hyperlinks, the first appearing in

Denver Area Educational Telecommunications Consortium, Inc. v.

FCC

30

from 1996. We checked the HTTP status for each citation,

finding that 63.6% returned a 200.

Over the following two days, our research assistants spot-checked

all links returning a 200, a refinement based on our earlier methodolo-

gy, using the original footnotes to determine the information that the

Supreme Court had intended to cite. Each link was coded by a single

research assistant.

Our finding is that 49.9% of the links cited in the Supreme Court

opinions no longer had the cited material. So again, while many of the

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

29

C

OURT

L

ISTENER

, https://www.courtlistener.com (last visited Feb. 26, 2013), archived at

http://perma.cc/0FXzJ8DpvKs.

30

518 U.S. 727 (1996).

2014] PERMA 187

links were technically valid — they did, in fact, return webpages —

many either did not contain the information originally cited or con-

tained information that had changed materially.

D

ISCUSSION

When devising a solution for link rot and reference rot, it is im-

portant to keep in mind the different reasons why a link may no longer

resolve properly. Other sources have documented many issues,

31

but

we will reiterate a few that we found in our work.

First, websites are often reorganized, and such reorganizations can

impact scholarship significantly. This is true even for websites of or-

ganizations that have a considerable influence on the law or have con-

siderable historical significance. For example, the International Crim-

inal Tribune for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) originally kept its

documents on a subpage of the United Nations website.

32

Many HRJ

articles referenced these documents, using those UN.org addresses. In

2001, the ICTY moved to ICTY.org, and all of the individual docu-

ment links now redirect to the top-level ICTY homepage.

33

That

change requires the reader to engage in a complex search to find an

original document again. Thus, and perhaps ironically, it is easier to

find documents related to war crimes that predate the “information

age” than documents about war crimes that were first published on the

Web.

34

Second, control of a website is sometimes handed over to a differ-

ent organization, again often creating havoc for citations. For exam-

ple, the overhaul of whitehouse.gov now results in all press release

links from the early 2000s redirecting to the home page for the White

House press office.

Third, the organizations or companies originally hosting the cited

material sometimes go defunct, either putting their domain names up

for sale, or ceasing to run servers. Or they go effectively defunct, if

only for a short period. The U.S. federal government, for example,

was partially shut down in late 2013, with thousands of formerly sta-

ble webpages at .gov destinations temporarily no longer available. Or

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

31

See, e.g., Frank McCown, Catherine C. Marshall & Michael L. Nelson, Why Web Sites Are

Lost (and How They’re Sometimes Found), C

OMM

.

ACM, Sept. 2009, at 141.

32

E.g. Prosecutor v. Rajic, Indictment (Int’l Crim. Trib. For the Former Yugoslavia Aug. 23,

1995), https://web.archive.org/web/20070528065139/http://www.un.org/icty/indictment/english/

raj-ii950829e.htm (last visited Feb. 26, 2014).

33

E.g. United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia,

http://www.un.org/icty/indictment/english/raj-ii950829e.htm (last visited Feb. 26, 2014).

34

For a list of the major print primary sources for the Nuremberg Trials, see Nuremberg Trials

Resources, H

ARV

. L

.

S

CHOOL

L

IBR

.

N

UREMBERG

T

RIALS

P

ROJECT

,

http://nuremberg.law.harvard.edu/php/docs_swi.php?DI=1&text=bibliogr (last updated Feb.

2003), archived at http://perma.cc/ZKD7-DYCC.

188 HARVARD LAW REVIEW FORUM [Vol. 127:176

they simply render the cited link useless. The URL ssnat.com, for ex-

ample, was originally cited in a 2011 Supreme Court case. Since 2011,

the site has become a commentary on the link itself: it now contains

only a message mentioning the Supreme Court opinion and musing

about the ephemerality of information.

35

Finally, and potentially most Orwellian, sometimes website owners

update the same page with new information and do not indicate that

the material has changed, or do not include the date of the update.

The White House, for example, has been charged with modifying press

releases, but has not indicated that the documents were changed.

36

And the Corporation for Public Broadcasting updates its website with

new information about the number of stations and affiliates it has.

However, because the update is not dated, it is not clear from the page

whether it has been updated since cited in FCC v. Fox Television Sta-

tions, Inc.

37

in 2009, thus producing a discrepancy between the fact on

the website and the fact as cited in the opinion. Commentators have

previously raised concerns about the mutability of web content, noting

that a blogger cited in a court opinion could edit the content to com-

pletely change it, or even add different facts or information.

38

Even

worse, sometimes the change is immediate, as when the website cited

is a database, meaning that every time someone clicks on a link, the

results are live.

These findings, and previous research, establish a compelling case

that link rot and reference-rot in online citations are significant and

increasing problems. Any solution to link and reference rot will have

to address the impermanence of the Web, the havoc caused by organi-

zational change (including webpage reorganization), handovers of do-

main names (and domain name sale), and successful citation practices.

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

35

When readers visit the link, they find a page that says “Aren’t you glad you didn’t cite to

this webpage in the Supreme Court Reporter at Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association,

131 S.Ct. 2729, 2749 n.14 (2011). If you had, like Justice Alito did, the original content would

long since have disappeared and someone else might have come along and purchased the domain

in order to make a comment about the transience of linked information in the internet age.” 404

Error — File Not Found, http://ssnat.com/, archived at http://perma.cc/0gwuqRxEJJW.

36

Scott Althaus & Kalev Leetaru, Airbrushing History, American Style, C

LINE

C

ENTER

FOR

D

EMOCRACY

(Nov. 25, 2008), http://www.clinecenter.illinois.edu/airbrushing_history, archived at

http://perma.cc/G8PW-798L.

37

129 S. Ct. 1800, 1836 (2009) (Breyer, J., dissenting).

38

See, e.g., Lee F. Peoples, The Citation of Blogs in Judicial Opinions, 13 T

UL

. J. T

ECH

.

&

I

NTELL

. P

ROP

. 39, 73.

2014] PERMA 189

A

DDRESSING

L

INK

R

OT

: P

ERMA

Given the distributed nature of the Internet, both link and refer-

ence rot is inevitable.

39

Based on the studies referenced above, and the

additional work we have done, it should be clear that both are serious

problems for scholarship.

Some researchers have suggested solutions for link rot, specifically

as applied to law reviews — following other scholarly fields by adopt-

ing Digital Object Identifiers (DOIs) in the citations of legal articles.

40

DOIs solve a number of problems with URL citation — they provide

the same level of traceability and persistence as a journal edition num-

ber or court citation while working for a variety of formats. For items

where a DOI will work or already exists, including scholarly works

and research datasets, a DOI in a citation can be very helpful.

DOIs have not gained traction within the legal community, howev-

er. Not only are they not suggested by The Bluebook, they are not

even mentioned by that citation resource at all.

41

DOIs may be a

promising solution for law review articles as printed volumes become

less and less popular, leaving citation to proprietary databases as the

alternative. However, for pages on the open web, a DOI system is im-

practical, requiring a high level of buy-in from document publishers

such as webmasters, bloggers, and newspapers, many of whom are

likely to be indifferent to the problems of posterity.

Another suggested solution includes using the Internet Archive to

preserve pages of scholarly importance. The Archive already repeat-

edly crawls as much of the Web as it can, preserving whatever it can

from what it finds.

42

This has some value for many links that are

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

39

Of course, conscientious website owners can take steps to prevent it. For example, when

moving to a new URL scheme or website organization, owners can keep old links with archived

previous versions of pages, or make the redirection process transparent. Realizing that govern-

ment-published materials may be widely cited, governments creating new URL schemes should

be especially careful to preserve the accessibility of older materials.

40

See Benjamin J. Keele, What if Law Journal Citations Included Digital Object Identifiers?

(Mar. 18, 2010) (unpublished manuscript), available at http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1577074; Su-

san Lyons, Persistent Identification of Electronic Documents and the Future of Footnotes, 97

L

AW

L

IBR

. J. 681 (2005).

41

This distinguishes The Bluebook and legal citation from many of the other citation styles in

other fields, which allow DOIs. In fact, the APA style requires the use of DOIs if available. See

P

UBLICATION

M

ANUAL

OF

THE

A

MERICAN

P

SYCHOLOGICAL

A

SSOCIATION

(6th ed. 2010);

T

HE

C

HICAGO

M

ANUAL

OF

S

TYLE

§ 14.6 (16th ed. 2010).

42

The Wayback Machine: FAQ, I

NTERNET

A

RCHIVE

, http://archive.org/about/

faqs.php#The_Wayback_Machine (last visited Feb. 26, 2014), archived at http://perma.cc/

0V2j3ibrkrG (“Why isn’t the site I’m looking for in the archive?: Some sites may not be included

because the automated crawlers were unaware of their existence at the time of the crawl. It’s also

possible that some sites were not archived because they were password protected, blocked by ro-

bots.txt, or otherwise inaccessible to our automated systems. Siteowners might have also request-

ed that their sites be excluded from the Wayback Machine. When this has occurred, you will see

190 HARVARD LAW REVIEW FORUM [Vol. 127:176

broken, and methods, including existing browser plug-ins, exist for re-

directing users to older versions of pages.

43

A standard to include

temporal information for archived pages, like the one suggested by the

team behind Memento, could make this effort even more effective.

44

However, the Internet Archive only occasionally trawls and stores

any given corner of the Internet, meaning there is no guarantee that a

given page would be archived to reflect what an author or editor saw

at the moment of citation. Moreover, the Internet Archive is only one

organization, privately funded and voluntarily supported, and there

might be long-term concerns around relying upon its continued exist-

ence. A system of distributed, redundant ownership and storage is ob-

viously a better long-term solution — and indeed, the Internet Archive

has shown itself ready to partner on archiving ventures in addition to

its own efforts.

45

Finally, some publishers and scholars have adopted an archiv-

al/permalink approach similar to the one described at the beginning of

this paper. For example, WebCite, a service run by Professor Gunther

Eysenbach at the University of Toronto, has been serving as a central

repository for caching documents for medical journals and other

sources for a number of years.

46

WebCite partially mitigates the issue

of sporadic archiving since individuals can create WebCite links di-

rectly, or journals can feed their archives through WebCite to save a

version of their pages.

But as with the Internet Archive, WebCite too is a single source so-

lution to a problem that could benefit from redundancy. Despite its

goal of permanence, the project has threatened to stop accepting new

URLs unless it receives donations.

47

Given the importance of scholar-

ly documents, the integrity of scholarship requires more assurance that

the archive will stay open.

Additionally, although WebCite allows for individuals to store pag-

es, its intake method for journal links means that there is no guarantee

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

a ‘blocked error’ message. When a site is excluded because of robots.txt you will see a ‘robots.txt

query exclusion error’ message.”).

43

See Adding Time to the Web, M

EMENTO

, http://mementoweb.org/ (last visited Feb. 26,

2014), archived at http://perma.cc/09Z5S1xWjLH; see also H. Van de Sompel, HTTP Framework

for Time-Based Access to Resource States, M

EMENTO

(Dec. 2013), http://www.mementoweb.org/

guide/rfc/ID/, archived at http://perma.cc/0XcKmZfbQat.

44

See Herbert Van de Sompel, Martin Klein, Robert Sanderson & Michael Nelson, Thoughts

on Referencing, Linking, Reference Rot, M

EMENTO

, http://mementoweb.org/missing-link/ (last

visited Feb. 26, 2014), archived at http://perma.cc/DUB4-VNYM.

45

See Archive-It — Learn More, I

NTERNET

A

RCHIVE

, https://archive-it.org/learn-more/ (last

visited Feb. 26, 2014), archived at http://perma.cc/W3T9-ZSH3.

46

WebCite Consortium FAQ, W

EB

C

ITE

, http://www.webcitation.org/faq (last visited Feb. 26,

2014), archived at http://perma.cc/0jRLzTskc8o.

47

See W

EB

C

ITE

, http://www.webcitation.org/ (last visited Feb. 26, 2014), archived at

http://perma.cc/0p7xfMNg8Kf.

2014] PERMA 191

that the material it is caching is the actual intended cited material.

Reference rot could have already occurred before caching, or the URL

cited could otherwise not return the expected material. For example,

larger and larger portions of the Web are personalized or display re-

gional content. The lack of a human element in ensuring the stored

material is what the author intended to cite is as much a problem for a

solution as it is for accurately measuring the extent of reference rot.

In addition to WebCite, there is another project already working in

this space — Archive.is, which advertises itself as a “personal Way-

back Machine” and contains a searchable archive of previously cap-

tured webpages.

48

Archive.is does not seem to suffer from the same

funding problems as WebCite, but may suffer from a lack of institu-

tional backing.

49

And it again is a single source solution, which is vul-

nerable to the changing mission of its founding organization.

P

ERMA

The solution we propose is a platform that will allow authors

and editors to automatically generate, store, and reference — in a

freely and publicly accessible manner — archived data representing

the relevant information of a cited online resource. A freely acces-

sible web database of cited materials will not only allow for the

owners of websites to no longer worry about maintaining cited

links, it will create better references and more easily verified

scholarship.

Just as a reference in a law review article published in the 1920s

is still retrievable today — at least with the help of a well-equipped

library — websites and online materials cited in today’s scholarship

should exist for verification indefinitely. And most importantly,

Perma is built with the support of a consortium of dozens of law

school libraries, as well as nonprofit entities such as the Internet

Archive and Digital Public Library of America, to ensure that links

to all cited materials will remain without change and in

perpetuity.

Perma uses the citation process itself as a solution to link rot.

As the author cites the material, the author can provide a link to

Perma, and the Perma server will save a copy of the information

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

48

A

RCHIVE

.

IS

,

http://archive.is/ (last visited Feb. 26, 2014), archived at

http://perma.cc/0yezTLau6VK.

49

See the Archive.is frequently asked questions page, which states, in part, “[Archive.is] is

privately funded; there are no complex finances behind it. It may look more or less reliable com-

pared to startup-style funding or a university project, depending on which risks are taken into

account. My death can cause interruption of service, but something like new market conditions

or changing head of a department cannot.” FAQ, A

RCHIVE

.

IS

, http://archive.is/faq.html (last vis-

ited Feb. 26, 2014), archived at http://perma.cc/0A72qhQbNAE.

192 HARVARD LAW REVIEW FORUM [Vol. 127:176

relevant to the citation — at that address at that particular time —

thereby capturing what the author determined was a source requir-

ing the citation. Perma will then return to the author a new link,

and a formal citation, which is designed to last as long as the Perma

system survives. That link can then be used in the work, either in

addition to the original citation, or instead of the original citation.

When a reader then follows the new permanent link, she will see

a number of pieces of basic metadata, in addition to the content

presently available at the original source. That metadata will in-

clude the time and date the author made the original citation, along

with the citing author and publication.

For dynamic or personalized content, Perma can retain a copy of

the content that the author originally experienced, at least to the ex-

tent it is relevant to providing a citable resource, and will not need

to rely on the original site to continue to serve content or material.

An author may also be able to upload a screenshot of content he or

she viewed, providing access to an advertisement or other piece of

content that would be hard to replicate by accessing the dynamic

page independently.

Perma will be designed to run harmoniously with paywalls and

other business models and practices common to the open Web.

When you access a Perma link, you will first be directed to the orig-

inal page; the Perma cache will only be accessed if the link no long-

er serves the original content. If for some reason the original site’s

content should not be displayed publicly, Perma will respect that by

only serving them up to users through a manual reference process

brokered by the hosting library.

50

Each institution using Perma will have an associated library

that vouches for the journal’s authenticity and scholarly value.

This design will help manage the number of cached links, as well as

demonstrate the libraries’ commitment to preservation of scholarly

works and sources. The project may also expand to other disci-

plines if additional libraries can support it. Perma will also support

the Memento protocol, allowing it to integrate into existing efforts

to allow recovery of cached webpages.

51

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

50

This process will permit sites archived by Perma to take down allegedly copyright-

infringing or defamatory material while allowing librarians to provide it to potential readers with

due care.

51

See M

EMENTO

, supra note 43; Chrome Web Store–Memento Time Travel,

https://chrome.google.com/webstore/detail/memento/jgbfpjledahoajcppakbgilmojkaghgm (last vis-

ited Feb. 26, 2014), archived at http://perma.cc/P6GP-GJZQ (describing and linking to the Me-

mento for Chrome extension that allows for page retrieval); Hvdsomp, Memento Extension for

Chrome: A Preview (Sept. 9, 2013), http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WtZHKeFwjzk (demon-

strating the use of the Memento for Chrome extension).

2014] PERMA 193

C

ONCLUSION

The rise of the Web has enabled the creation and exchange of

scholarly knowledge and the sources on which it is based. It has

also bypassed the libraries that previously vouchsafed the long-term

preservation of those sources. Unless action is taken to archive this

type of information, future readers will be unable to obtain the

sources relied upon by the authors whose work they read. The in-

tegrity of scholarship will suffer. The distributed Perma system

seeks to unite journals, libraries, and authors to restore that integri-

ty by ensuring that those sources are appropriately preserved for

posterity.

194 HARVARD LAW REVIEW FORUM [Vol. 127:176

A

PPENDIX

1: R

ELEVANT

HTTP S

TATUS

C

ODES

52

10.2.1 200 OK

The request has succeeded. The information returned with the

response is dependent on the method used in the request, for

example:

GET an entity corresponding to the requested resource is sent in

the response;

HEAD the entity-header fields corresponding to the requested

resource are sent in the response without any message-body;

POST an entity describing or containing the result of the action;

TRACE an entity containing the request message as received by

the end server.

10.4.1 400 Bad Request

The request could not be understood by the server due to mal-

formed syntax. The client SHOULD NOT repeat the request

without modifications.

10.4.2 401 Unauthorized

The request requires user authentication. The response MUST

include a WWW-Authenticate header field (section 14.47) contain-

ing a challenge applicable to the requested resource. The client

MAY repeat the request with a suitable Authorization header field

(section 14.8). If the request already included Authorization creden-

tials, then the 401 response indicates that authorization has been re-

fused for those credentials. If the 401 response contains the same

challenge as the prior response, and the user agent has already at-

tempted authentication at least once, then the user SHOULD be

presented the entity that was given in the response, since that entity

might include relevant diagnostic information. HTTP access au-

thentication is explained in “HTTP Authentication: Basic and Di-

gest Access Authentication.”

53

10.4.4 403 Forbidden

The server understood the request, but is refusing to fulfill it.

Authorization will not help and the request SHOULD NOT be re-

peated. If the request method was not HEAD and the server wish-

es to make public why the request has not been fulfilled, it

SHOULD describe the reason for the refusal in the entity. If the

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

52

Excerpted from Fielding et al., supra note 23.

53

J. Franks et al., HTTP Authentication: Basic and Digest Access Authentication, I

NTERNET

E

NGINEERING

T

ASK

F

ORCE

(June 1999), http://tools.ietf.org/pdf/rfc2617.pdf, archived at

http://perma.cc/5TMQ-64KF.

2014] PERMA 195

server does not wish to make this information available to the cli-

ent, the status code 404 (Not Found) can be used instead.

10.4.5 404 Not Found

The server has not found anything matching the Request-URI.

No indication is given of whether the condition is temporary or

permanent. The 410 (Gone) status code SHOULD be used if the

server knows, through some internally configurable mechanism,

that an old resource is permanently unavailable and has no for-

warding address. This status code is commonly used when the

server does not wish to reveal exactly why the request has been re-

fused, or when no other response is applicable.

10.4.6 405 Method Not Allowed

The method specified in the Request-Line is not allowed for the

resource identified by the Request-URI. The response MUST in-

clude an Allow header containing a list of valid methods for the re-

quested resource.

10.4.11 410 Gone

The requested resource is no longer available at the server and

no forwarding address is known. This condition is expected to be

considered permanent. Clients with link editing capabilities

SHOULD delete references to the Request-URI after user approval.

If the server does not know, or has no facility to determine, whether

or not the condition is permanent, the status code 404 (Not Found)

SHOULD be used instead. This response is cacheable unless indi-

cated otherwise.

The 410 response is primarily intended to assist the task of web

maintenance by notifying the recipient that the resource is inten-

tionally unavailable and that the server owners desire that remote

links to that resource be removed. Such an event is common for

limited-time, promotional services and for resources belonging to

individuals no longer working at the server’s site. It is not neces-

sary to mark all permanently unavailable resources as “gone” or to

keep the mark for any length of time — that is left to the discretion

of the server owner.

10.4.17 416 Requested Range Not Satisfiable

A server SHOULD return a response with this status code if a

request included a Range request-header field (section 14.35), and

none of the range-specifier values in this field overlap the current

extent of the selected resource, and the request did not include an

If-Range request-header field. (For byte-ranges, this means that the

first-byte-pos of all of the byte-range-spec values were greater than

the current length of the selected resource.)

196 HARVARD LAW REVIEW FORUM [Vol. 127:176

When this status code is returned for a byte-range request, the

response SHOULD include a Content-Range entity-header field

specifying the current length of the selected resource (see sec-

tion 14.16). This response MUST NOT use the multi-

part/byteranges content-type.

10.5.1 500 Internal Server Error

The server encountered an unexpected condition which prevent-

ed it from fulfilling the request.

10.5.3 502 Bad Gateway

The server, while acting as a gateway or proxy, received an inva-

lid response from the upstream server it accessed in attempting to

fulfill the request.

2014] PERMA 197

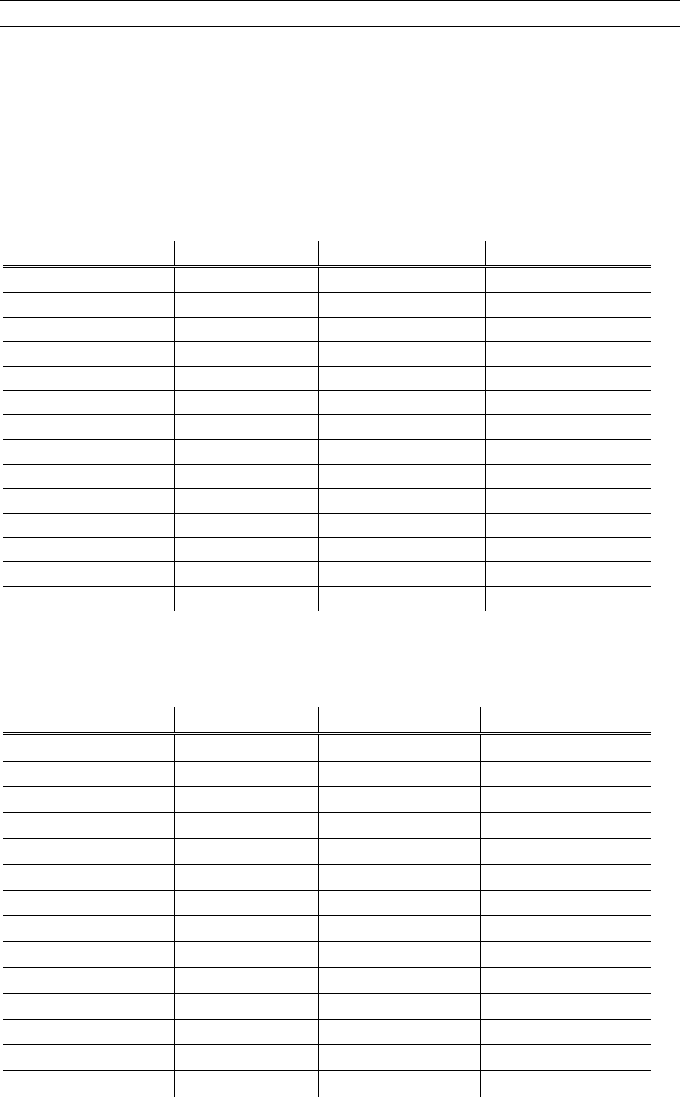

A

PPENDIX

2: B

REAKDOWN

OF

HTTP

S

TATUS

C

ODES

BY

J

OURNAL

HRJ

Code Frequency Percentage Cumulative

200 1,412 59.88 59.88

404 736 31.21 91.09

OPEN 150 6.36 97.46

403 21 0.89 98.35

400 11 0.47 98.81

500 11 0.47 99.28

302 4 0.17 99.45

502 3 0.13 99.58

UNKNOWN 3 0.13 99.7

303 2 0.08 99.79

401 2 0.08 99.87

410 2 0.08 99.96

415 1 0.04 100

To t al 2,358 100

HLR

Code Frequency Percentage Cumulative

200 3,855 65.22 65.22

404 1,543 26.1 91.32

OPEN 362 6.12 97.45

403 78 1.32 98.77

400 23 0.39 99.15

500 23 0.39 99.54

302 10 0.17 99.71

UNKNOWN 6 0.1 99.81

410 5 0.08 99.9

301 2 0.03 99.93

401 2 0.03 99.97

300 1 0.02 99.98

503 1 0.02 100

To t al 5,911 100

198 HARVARD LAW REVIEW FORUM [Vol. 127:176

JOLT

Code Frequency Percentage Cumulative

200 3,627 66.82 66.82

404 1,190 21.92 88.74

OPEN 377 6.95 95.69

403 177 3.26 98.95

500 15 0.28 99.23

400 8 0.15 99.37

302 5 0.09 99.47

410 5 0.09 99.56

503 5 0.09 99.65

401 4 0.07 99.72

UNKNOWN 4 0.07 99.8

300 3 0.06 99.85

400 8 0.15 99.37

301 3 0.06 99.91

415 2 0.04 99.94

303 1 0.02 99.96

416 1 0.02 99.98

502 1 0.02 100

To t al 5,428 100

2014] PERMA 199

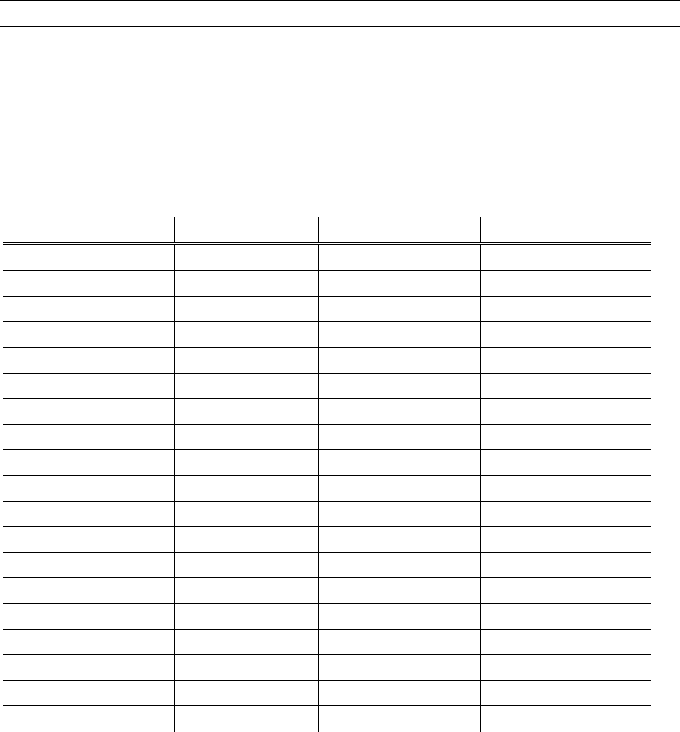

A

PPENDIX

3: B

REAKDOWN

OF

200 S

TATUS

C

ODE

T

AGS

BY

J

OURNAL

HRJ

Tag Frequency Percentage

200–Working 195 64.36

200–Redirect 67 22.11

200–Custom 404 22 7.26

200–Blank Page 8 2.64

200–Domain for Sale 4 1.32

200–Assorted Error 3 0.99

200–Archived 2 0.66

200–Paywall 2 0.66

To t al 303

HLR

Tag Frequency

Percentage

200–Working 237

67.71

200–Redirect 49

14.00

200–Custom 404 39

11.14

200–Working (updated) 22

6.29

200–Domain for Sale 2

0.57

200–Unclear 1

0.29

200–Paywall 1

0.29

To t al 350

JOLT

Tag Frequency

Percentage

200–Working 228

65.52

200–Redirect 53

15.23

200–Custom 404 28

8.05

200–Working (updated) 27

7.76

200–Blank Page 4

1.15

200–Domain for Sale 2

0.57

200–DNS Lookup Failed 2

0.57

200–Archived 1

0.29

200–500 Error 1

0.29

200–Forbidden 1

0.29

200–Paywall 1

0.29

To t al 348